19th January 2023

A question we regularly get asked by our clients is ‘why do you currently have low exposure to US equities?’ The short answer: extremely high valuations produce dismal long-term outcomes – and aggregate US valuations are extremely high.

The long answer is as follows and is easiest to bring to life by using an example.

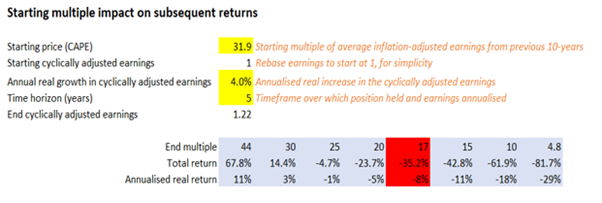

Below we present a real returns model (as investors our focus is on real returns ie after inflation) using the Shiller PE for the US market. As a reminder, the Shiller PE takes the average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years as the denominator in the ratio – so is already operating in the real world, whilst taking the 10 year earnings average aims to capture a full market cycle so mitigates issues around valuing equities on peak or trough earnings.

I am keeping things simple by assuming no dividends (the dividend yield on the US market is very low anyway, around 1%). So, the returns you can expect to get are a function of the starting multiple of earnings, the end multiple of earnings, and the change in earnings in the interim.

So, what to plug in to the valuation model? Let’s use history as a guide:

- The very long-term average Shiller PE for the US market (over 150 years of data) is 17x. The past c.30-year average in the US CAPE has been closer to 25x. The lowest multiple was 4.8x in December 1920, and the highest was 44x in December 1999.

- The current multiple is a hefty 31.9x, nearly double that very long-term average, and nearly 30% above the 30-year average.

- The annual real growth in cyclically adjusted earnings over the past 20 years has been 3.9% per annum. Over c.150 years, it is closer to 2% per annum.

The table below shows the real return expectation taking a 5-year time horizon with different end multiples. It assumes that earnings can continue to compound at 4% per annum in real terms, double the long-term average despite margins in the US starting from a point of all-time highs. Even with that, it’s not pretty. If we assume earnings revert to the long-term average of just 2%, it gets even uglier.

If multiples revert to the long-term average of 17x, you will lose 8% in real terms per annum over the next 5 years. Even if they just revert to the 30-year average of 25x you lose money in real terms.

Now let’s bring some more context to those return prospects – what else can we choose to deploy capital into?

- We could guarantee a positive real return in USD terms from investing in US TIPS (the 5-year real yield is at +1.7%, ie you can make c.8.7% real by simply owning a 5-year TIPS to maturity).

- We can invest in UK equities at historically cheap levels – levels from which historically the market has delivered very attractive returns over subsequent 5-year periods.

- We can invest in Asian and emerging market equities at historically cheap levels with very attractive starting dividend yields of 6-9%

- We can invest in Japanese equities which are enjoying a wave of corporate governance improvements unlocking significant returns for shareholders.

- We can invest in corporate bonds offering high nominal (and likely high real) returns.

- We can invest in deeply discounted investment trusts with clear catalysts to realise significant returns.

- We can invest in high quality property and infrastructure trusts with attractive real return prospects that in many cases should be uncorrelated to broader markets.

So, the question we would pose back is why should we take the huge multiple risk in the US market today? With c.70% of global equity markets represented by the US market, many investors are very much exposed to this valuation risk, so we feel this is a very relevant question.

Market history is riddled with examples of extremely high valuations producing dismal long-term outcomes for investors. The US market itself has historically gone through very long periods where the returns generated from its equity market have lagged the returns on Treasury Bonds. John Hussman produces excellent research on US valuations, and in a recent blog noted that between 1929-1947, 1968-1985 and 2000-2013 the total return of the S&P 500 lagged the total return of Treasury Bills. The starting multiple for US stocks today has only been exceeded by the peak of the dot com bubble and the very briefly in 1929. We accept that over short time horizons valuations are a poor predictor of returns, but they matter a lot over the medium to long term.

It is worth pointing out that the above is focused on US valuations in aggregate, which is skewed by the US market being heavily concentrated in a few very large stocks which are particularly expensive. We do have some US equity exposure in our funds, and there are some very good active managers in the US looking beyond the biggest stocks where there are many attractively valued companies that are primed to deliver attractive real returns in the coming years.

Dan Cartridge – Assistant Fund Manager

For professional advisers only. This article is issued by Hawksmoor Fund Managers which is a trading name of Hawksmoor Investment Management (“Hawksmoor”). Hawksmoor is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Hawksmoor’s registered office is 2nd Floor Stratus House, Emperor Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS. Company Number: 6307442. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person, nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice for which you should consult your financial adviser and/or accountant. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Any opinion expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation and may be subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations. You may not get back the amount you originally invested. FPC1342.