Buy, buy, says the sign in the shop window

Why, why, says the junk in the yard

– Paul McCartney, Junk (1970)

2018 was a seminal year for recycling. The national conscience has finally awoken to the demanding issues of environmental sustainability, the impact plastic waste has on the world’s marine life (with at least some credit due to Blue Planet II ) and a belated realization that our waste is not someone else’s problem.

Concurrently – and another key reason why plastic waste is suddenly top of the national agenda – are the consequences of China’s “National Sword” policy. This policy is rewriting the rules of the recycling game in profound ways.

National Sword

For decades, developed nations have used China as a dumping ground for their excess waste. In 2017 China processed 55% of the world’s scrap paper and imported 3.5 million metric tonnes of scrap plastic. Virtually all UK plastic recycling is exported: and China used to be the main buyer.

Yet with mounting concerns over air quality, pollution and illegal waste smuggling, the Chinese government launched National Sword, a campaign against jang laji (“foreign garbage”). Crucially, from January 2018 this policy banned outright the importation of 24 types of waste materials and set much higher contamination standards for the rest.

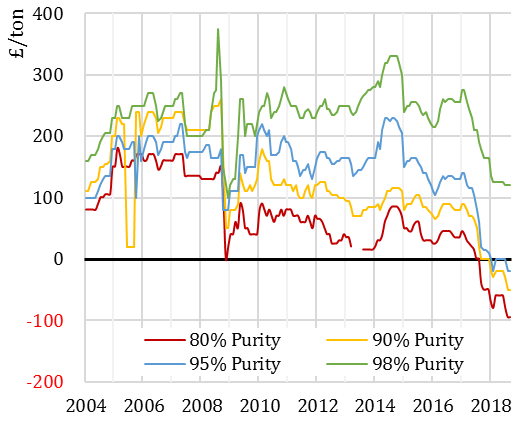

The market impact was savage. With the key buyer of scrap paper and plastic removed, prices collapsed (Chart 1). That took much of the profitability away from the UK’s Material Recovery Facilities, which take in raw recyclable waste, separate and process it into a commodity. That loss of revenue has only been partly mitigated by higher gate fees levied on the collectors of waste.

Chart 1: Recycled plastic prices, Jan 2004 to Sept 2018

Source: LetsRecycle.com

A step backwards

The challenge of National Sword is exacerbated in Britain due to the relative immaturity of our recycling infrastructure. Our curb-side recycling collections are mostly mixed: though sorted, contamination is naturally high and that produces a low-grade commodity. Our European cousins are much better at this. The importance is that National Sword increases standards from 90–95% purity to 99.5%. Notice in Chart 1 that purer recycling grades are attributed higher prices and that this year prices for lower grades actually turned negative.

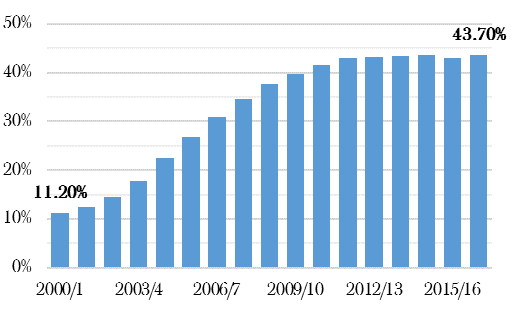

Some of that excess has gone to other Asian markets, such as India, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand, pushing them past capacity. We know 90% of the plastic in the oceans comes from ten rivers, eight of which are in Asia. Otherwise, after decades of positive progress (Chart 2), more of our recyclable waste is at risk of simply ending up in landfill.

Chart 2: Household waste recycling rate in England

Source: Defra Statistics¸ 2000/01 to 2016/17

In summary, the UK became accustomed to exporting relatively low-grade recyclate to the Far East. There hasn’t been the pressure to invest in our own recycling facilities, segregated collections or better sorting technologies. With the main buyer now regulated out of the market, that has to change. The UK needs to invest in its own recycling industry to realize a self-sufficient circular economy.

Energy from Waste

One of the alternatives to recycling our waste, or burying it in the ground, is to use it to generate electricity: an easily obtainable fuel that diverts materials going to landfills. Indeed, even existing landfill sites are today generating electricity through the trapping of methane gas emitted as the waste decomposes.

Yet be under no illusions: Energy Recovery Facility is generally a euphemism for incineration. That means emissions of toxic and hazardous pollutants: to produce 1MWh of electricity, an ERF produces more than twice the carbon dioxide than a natural gas plant. Around 25-30% of the waste remains as residual ash to be disposed of or stored and, of course, there is nothing circular about destruction.

Recycling in the UK

Certain materials are simply easier to recycle. Packaging group DS Smith, for example, operates nine cardboard recycling facilities in the UK. As well as producing boxes, it collects, sorts and recycles cardboard from its customers to make new boxes. It is a complete circular economy model: DS Smith claims this cycle repeats every 14 days.

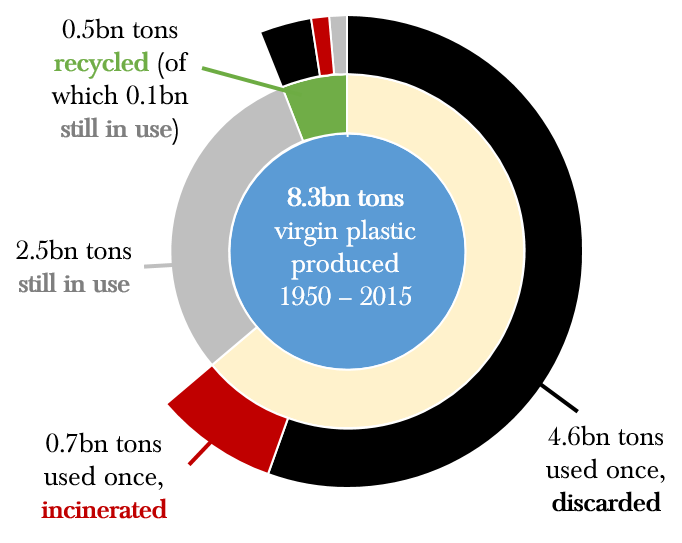

Plastic is more difficult (Chart 3), not least because there are over 50 different types – such as PET, HDPE, PP and PVC – that generally need to be sorted and processed separately. There is some incremental investment already happening in the UK: Biffa, for example, recently unveiled a £15m plan to open a PET recycling plant with an output of 25ktpa. However, it is small in comparison to that set aside for Energy for Waste: at the same time, Biffa is involved in a £270m project for 350ktpa of energy recovery plant. Our concern is that the economics of Energy from Waste are crowding out the investment and environmental needs of pure recycling plants.

Naturally, commercial organisations need assurance on the economics of projects and demand for recycled material before investing. We expect visibility on this to improve in coming years, especially with the introduction of a new tax on packaging containing less than 30% recycled content. Indeed, the tax’s stated intention is to make prices ‘so exorbitantly high’ that companies would simply conclude virgin plastic packaging was no longer worthwhile.

Chart 3: “Fate of all plastics ever made”, 1950 – 2015

Source: R. Geyer et al., Science Advances

Then there is China: its economy will still have a huge appetite for plastic and cardboard. There are parallel repercussions of National Sword occurring within China and there has been little time to adjust. Instead of sending containerships of old boxes and bottles, perhaps in future we will send papers and plastics we have recycled ourselves.

Investment Considerations

Our core thesis is that the changes to the recycling landscape in 2018 pave the way for a significant improvement in the UK’s recycling infrastructure and technology base.

Naturally, this will create incremental construction work to build the recycling and energy recovery facilities. Yet this is not without significant risks: Interserve ran into huge financial difficulties building a Glaswegian Energy from Waste plant for Viridor. Construction is an industry with razor thin margins where complications, particularly when utilising new technology, can quickly turn contracts onerous.

UK-listed operators of waste facilities include Biffa, Pennon and Renewi. A greater need for recycling activity in the UK creates a structural growth opportunity for these businesses, especially when supported by government policy. However, these projects will require hefty inward investment: it will take time for that to translate into returns.

Our preference is to invest in the manufacturers of the equipment and the innovators of the technology. In August this year, Viridor announced it had installed a robotic sorter in its Skelmersdale facility that uses artificial intelligence and vision to identify recyclables and make decisions. Elsewhere, several firms are developing chemical processes to break down plastics back into some form of oil.

Direct investment options in the UK are limited: most are small private companies. We therefore prefer to access this theme via funds. As just one example, the Jupiter Ecology fund, which features in our Sustainable World service, holds a stake in TOMRA Systems, a US company pioneering sensor-based materials sorting.

Final thoughts

National Sword is hugely disruptive in the short-term, though at the same time offers a real opportunity for the UK to finally take responsibility for its waste. We want to invest in those companies at the forefront of transitioning our economy to a more sustainable future.

Ian Woolley and Ben Luck, Hawksmoor Research

Health Warning/ Disclaimer

This document should not be interpreted as investment advice for which you should consult your independent financial adviser. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Any opinion expressed, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation. They are subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited is registered in England No. 6307442 and its registered office is at 2nd Floor, Stratus House, Emperors Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter EX1 3QS. HA3019

FOR PROFESSIONAL ADVISERS ONLY AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED UPON BY RETAIL INVESTORS