You have to love August. It is a fine silly season this year. The top story – so far – has to be Donald Trump wanting to buy Greenland. And congratulations to the Wall Street Journal for pointing out that this is not going to happen as the golf courses are only open for four months a year.

Then we have the Adrian Darya sailing out of Gibraltar, without charge and with oil. And now desperately trying to prove that it wasn’t really going to Syria. And Russia has had a major nuclear incident. In the race to develop first-strike capability via a nuclear-powered nuclear missile, the sky has fallen on Russia’s Skyfall. It is a brilliant post-modern Cold War story, unless one lives in Nyonoksa.

We have been bleating for too long about the unresolved tension between bond and equity markets. And my apologies for the awful misquote in this week’s title, but it fits the argument rather better than Shakespeare’s inferior original (smiley emoticon). Last week saw a little outbreak of sanity, though the causes may have been dubious. US equities fell by 3% (or so) last Wednesday, reportedly triggered by the basis point niceties of the yield curve. The fad of the week was the global 2-10 year spread, which by virtue of being inverted by one basis point, apparently foretells that the four horsemen have saddled up.

It is, to be fair, getting a bit silly. The collapse in bond yields is becoming self-fulfilling: everyone now accepts that yields are a one way bet, without being exactly sure why. The economic numbers have been weakening for a while, but they are not THAT bad (with apologies for the gratuitous over-emphasis). Germany’s 10 year yield, for example, is the lowest ever. For the sake of stating what has already been stated, that means they are lower now than in the worst of the Great Financial Crisis and the height of QE. How does that work? The bund yield is saying that we have a crisis worse than the worst crisis of modern capitalism.

The UK 30 year yield touched 1% last week. The bottom of the UK curve is 7 years, which is 34bps. Meaning we are 35bps from negative gilt yields. I am naturally reticent about the use of the term ‘bubble’, but this is one: there is massive groupthink, manifest in the gross confirmation bias taken from any weak economic data. Now let us throw in the credibility of a sound starting point of genuinely weakening data, plus the unquantifiable multiplier of the trade wars (and Brexit).

Sovereign bond markets are ticking so many of the bubble boxes. So here is a scenario for the autumn, and winter: yields keep falling, and curves inverting. This will prompt a co-ordinated central bank response and aggressive easing of policy, which will then call the turning point of this cycle.

There are more pennies to be picked up in front of the steamroller of reality. It was Keynes who first argued that markets will remain insane longer than investors can stay solvent. Our pain in having small allocations to sovereign bonds is that of opportunity cost. The majority of our bond funds are performing adequately and rationally. They merely lag in the face of the mania of sovereign yields.

Do you remember the UK wage and employment numbers from earlier on last week? Wage growth is at an 11 year high (3.9% absolute, reported as 1.9% real); a record 32.81m people are in work. How does that square with the market’s lust for zero gilt yields?

Perhaps the answer is in Operation Yellowhammer. Someone has supplied the Sunday Times with some central assumptions about No Deal. None of these will come as a tremendous surprise, and they broadly fit my much-used Ghostbusters reference of ‘it would be bad’.

But dashing back to the bond yield thing, I just want to make a quick reference to money supply. The theoretical role of money in determining such trivia as inflation and growth rates is broadly dismissed by aggressive Keynesian groupthink in the central banks. I would argue this wouldn’t I, but surely that makes it all the more relevant. Anyway, the messages being ignored by the banks are that the UK is indeed in a pickle, the US is in good form, as is, surprisingly, the Eurozone. Emerging markets, especially India and China, are in good health.

Well done to all those who discovered that the two features of bearded tit are that neither does it have a beard, nor is it a tit. Today, the word ‘ushers’ contains five examples of what (other than different letters, thank you Ian)? Enjoy the Bank Holiday.

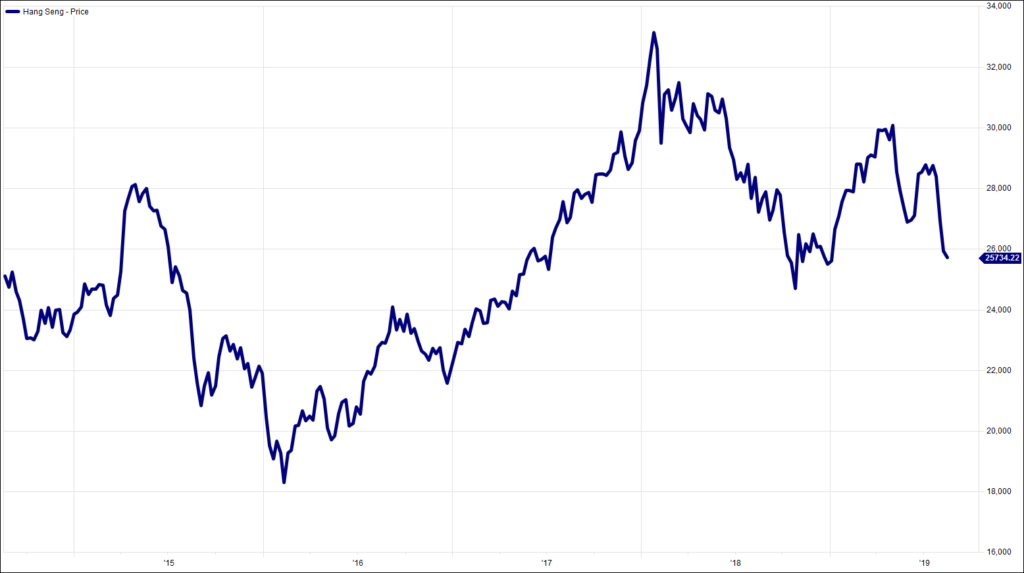

Chart of the Week:

Hang Seng, past 5 years. I predict a riot.

HA804/224

All charts and data sourced from FactSet

Jim Wood-Smith – CIO Private Clients & Head of Research

Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (www.fca.org.uk) with its registered office at 2nd Floor Stratus House, Emperor Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person in respect of the securities or funds described, nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice for which you should consult your independent financial adviser and or accountant. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. The editorial content is the personal opinion of Jim Wood-Smith, CIO Private Clients and Head of Research. Other opinions expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represent the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation and may be subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations. You may not get back the amount you originally invested. Currency exchange rates may affect the value of investments.