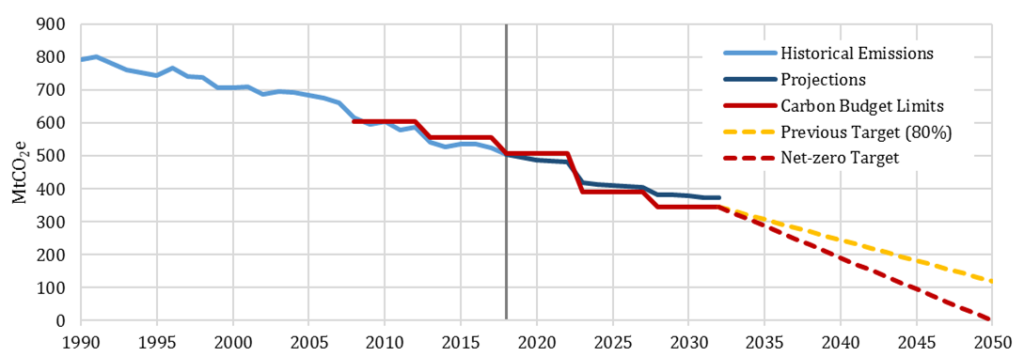

In April 2019, the statutory body that advises the government on preparing for climate change declared that the UK should target net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. For some, the Committee on Climate Change’s (CCC) recommendation is outrageously ambitious; even the prior 2050 target of an 80% reduction in emissions relative to 1990 seemed a Herculean challenge (Chart 1). For others – most vociferously the Extinction Rebellion protesters – a 2050 net-zero target is not nearly urgent enough and must come decades earlier.

Our emission targets form from a patchwork of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the 2008 Climate Change Act and, most recently, the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Though to date these budgets have been met or exceeded, the UK is currently not on track to meet the 2023-2027 target. Meanwhile, a 2050 net-zero target would require even greater changes to policy and our daily lives (Chart 1).

Chart 1: UK Emissions: historic, projections and targets

Source: BEIS

The added nuance to the CCC’s recommendation is its renewed call to include aviation and shipping in the emission target. Critics, such as Greta Thunberg, accuse the UK Government of “very creative carbon accounting” by narrowly reporting progress on only territorial emissions: it is all too easy to shift responsibility overseas. Climate change is after all a global, not a territorial, problem. Were the CCC’s revised definition adopted, that net-zero target is all the more difficult to achieve from here. Either way, the extent of change required for the UK to stay in budget is huge.

“If the meticulous and robust expert advice here is heeded it will deliver a revolution in every facet of our lives, from how we power our homes and travel to work to the food we buy.”

– Prof David Reay, University of Edinburgh (May 2019)

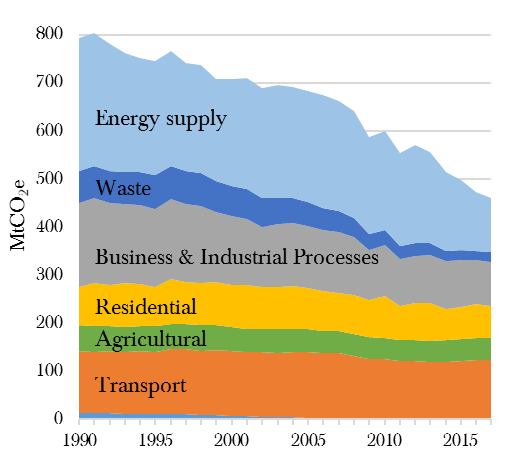

Chart 2: UK Emissions by sector, 1990 – 2017

Source: BEIS

Beneath the surface, the energy sector has done much of the UK’s emission-reduction heavy lifting to date (Chart 2 above). Specifically, the reduced use of coal for electricity generation has meant a 60% decrease in energy supply emissions. Other sectors have been less amenable: transport emissions are broadly flat and are now the biggest contributor (27%). There has also been precious little progress in residential or agricultural. That means that for the past thirty years, the UK has met its emissions targets with very little disruption to UK households.

In the coming decades that has to change. The CCC urges policymakers to look to buildings, transport, lifestyles and agriculture for further emission reductions. The French may nickname us les rosbifs, but the CCC warns our diets should contain 20% less beef, lamb and dairy to help reduce agricultural emissions.

Aviation too is problematic. Unlike car fuel, there are not yet viable alternatives to jet fuel, which must be able to combust in temperatures as low as –30°C. Yet measures to curb demand for flights will not be popular in a nation accustomed to an annual worship of Iberian sun.

Cleaning up after ourselves will inevitably come at a cost. The CCC estimates that the cost to the UK to achieve net-zero by 2050 is 1–2% of GDP annually. This week, the Chancellor Philip Hammond pointed out that this is over £1 trillion. The CCC’s policies would demand public spending and borrowing, channelling funding away from other priorities like schools and hospitals. It might also mean higher energy and living costs for families.

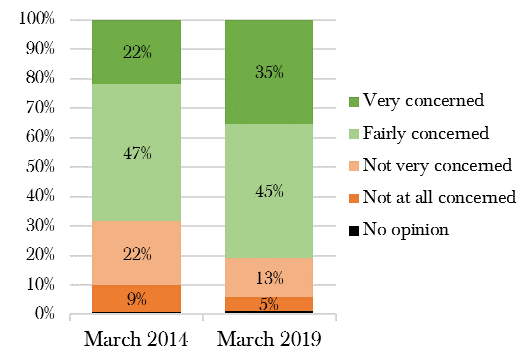

Hammond fails to mention, however, that it will be even more expensive to reach net-zero the longer we wait: removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere once released is extremely costly. He further fails to acknowledge the benefits of less pollution and new green industries and jobs, or the increasing levels of public concern about climate change (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Public concerns about climate change in the UK

Source: BEIS Public Attitudes Tracker, March 2019

If we therefore conclude that change is coming, what does change look like? 75GW of offshore wind, up from 8GW today. The electrification of transport and heating, resulting in a doubling of electricity demand. A transition away from gas boilers for 29 million existing homes. Better insulation, windows and draught proofing. Installing 1,200 rapid chargers near major roads, and a further 27,000 in towns across the country. Mass afforestation in the UK with the planting of 30,000 hectares of trees every year. The development of a carbon sequestration industry.

It should be unsurprising that decarbonization is a major theme for a number of the funds in our Sustainable World services. As we have discussed, the opportunities are vast. The Liontrust Sustainable Future range of funds, for example, invest across three broad themes and twenty sub-themes including improving the efficiency of energy use and making transportation more efficient. Holdings include Kingspan, the Irish manufacturer of insulated panels and other energy-efficient building materials, and Hella, a German manufacturer of auto components including auto-dimming energy-efficient LED highlights.

Elsewhere, John Laing Environmental Assets owns and operates a portfolio of environmental infrastructure assets across wind, solar, waste and wastewater, and anaerobic digestion. Such is the growing opportunity set that this trust has recently raised equity several times.

Yet while decarbonization brings opportunity for some, it delivers existential disruption for others. Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, states that a carbon budget consistent with the 2015 Paris Climate Change Agreement “would render the vast majority of reserves ‘stranded’ — oil, gas and coal that will be literally unburnable without expensive carbon capture technology, which itself alters fossil fuel economics”. Those lending to, or investing in, fossil fuel producers should sit up and take notice. How flexible can these firms be in adapting to a low-carbon economy? Does the current management team have a credible plan?

The implications of the 2015 Paris Climate Change Agreement are dramatic. For investors, the question should be how to position portfolios to benefit from the growth opportunities within the green economy of the future, and side step those facing low-carbon oblivion.

For the UK to meet its legal emission obligations, react to growing public concern about climate change, and reach the position of no longer contributing to global warming by 2050, it will have to expedite major changes to our day-to-day lives. That, in turn, yields an outlook for vastly varying fortunes for different businesses: opportunity for some, but existential threat for others. Investors ignore the implications of the decarbonization shift at their peril.

Ian Woolley – Senior Investment Analyst

Health Warning/ Disclaimer

This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person, nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice. The information and opinions herein are compiled from sources believed to be reliable at the time of writing and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy (completeness or correctness). Any opinion expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation and may be subject to change (past performance is not a guide to future performance).

Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Hawksmoor’s registered office is 2nd Floor, Stratus House, Emperors Way, Exeter Business Park EX1 3QS. Company No.: 6307442. HA3344

FOR PROFESSIONAL ADVISERS ONLY AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED UPON BY RETAIL INVESTORS