Snakes and Ladders

There has been a steady pattern to our quarterly reports over recent years. Broadly, equity markets will have risen and we then do our level best to explain why there is still plenty that worries us. The tables turned in the first three months of this year: equity markets wobbled and we argued that this should not be a cause of lost sleep. Apparently whichever way markets move, we try to persuade you why this ought not to have happened. Over the course of the first half of the year, however, we have been down a snake and up a ladder, to finish pretty much where we started. For a change, that feels about right.

The second quarter of the year saw much huffing and puffing. Most of this had a single source and we shall return to Mr Trump later. The two most important issues of the quarter, however, were the rises in the US dollar and the price of oil. Both of these have potentially significant ramifications.

the second quarter of the year saw much huffing and puffing

For us, there are two major drivers behind the new popularity of the dollar. Leading the way is the Federal Reserve’s determination to raise American interest rates. On balance, data suggest that the pace of growth of the US economy rose in the second quarter. Faster growth means more jobs, higher employment levels mean companies have to pay workers more and that, so the argument runs, will create inflation. That at least is the very simple economics argument that is driving American monetary policy. A 2% yield on 3 month Treasury Bills undoubtedly has its attractions and it is not hard to see why everyone currently wants to buy dollars.

It is accepted wisdom that a strong dollar adversely affects Emerging Markets. Currencies, equity and bond markets of these collective countries tend to fall disproportionately when the dollar rises. The explanation is straightforward enough: Emerging Markets tend to borrow US dollars (as well as their own currencies). Thus when the dollar goes up, so does the cost of their interest payments. Higher interest payments stress public finances and global investors run away.

Regular readers will be well aware of our profound scepticism of accepted wisdoms. This time however, the rule has held good. There have been specific issues regarding Turkey, Argentina and Brazil, but everyone is tarred with the same brush when the dollar is strong. Emerging Markets have been a drag on performance this year and may well continue to do so for a little while longer. Our longer-term enthusiasm may be undimmed, but some additional shorter-term caution may be practical.

There is a second driver for the dollar, however, which takes us back to Mr Trump. Just as part of the strength of the US economy can be attributed to the Republicans’ tax cuts, so some of the credit for the dollar lies at the same door. American companies have a window of opportunity in which they can repatriate their overseas stockpiles of cash at reduced tax rates and they are bringing it home by the boatful. There is little patriotic about this, however. The cash is being used to fund record levels of share buybacks, not investment. Buybacks may support share prices, but that is secondary to helping management achieve remuneration targets based on growth of earnings per share, and thus their treasured wallets.

The second significant development for financial markets has been the rise in the price of oil. For those of us who drive too many miles, the increase in the cost of fuel has been significant. The reasons behind it are unclear. Mr Trump (he again) has not helped with his demonization of Iran, while the financial collapse of Venezuela has added to the pressures on global production. It is though somewhat perplexing that the price has moved so much at a time when the global economy remains so robustly uninteresting. One credible explanation is perhaps that Saudi Arabia has been subtly squeezing the price up ahead of its much-vaunted 2019 flotation of Aramco, the state-owned oil company. Experience has taught that it is best to accept the oil price, rather than to predict it.

The most tangible impact of oil on stock markets was a significant rise in the share prices of the oil producers. Royal Dutch Shell and BP make up a considerable proportion of the worth of the UK market. The share prices of both rose (in round numbers) by 25% between March and May, a staggering change in the markets’ assessment of their value over the course of a mere couple of months. We may be heading inexorably to an era of renewable power and electric vehicles, but it is too early to take one’s pew for the reading of oil’s eulogy.

the lesson from 2016 was not to bet the farm

We have thus far avoided the B word. As we write, in early July, the UK’s progress towards the European departure gate is shrouded in just as much fog as ever. The Cabinet Office has revolving doors and all possibilities remain on the table. From the perspective of the market these range from the disastrous ‘no deal’, to its favoured outcome of a second referendum and vote to remain. Somewhere in the mix, there is also the scenario of an election and a Corbyn government.

It may be tempting to say that the UK is heading towards a sterling crisis – and to adjust portfolios accordingly – but we cannot simply rule out the possibility of the polar opposite. The lesson from 2016 was not to bet the farm one way or the other: we are thus tilting towards the likelihood of further falls in the pound, but not to the extent of the value opportunities in domestic stocks. Occasionally, resting on a fence is the right thing to do.

We do not expect financial markets overall to make significant advances until there is greater clarity surrounding American interest rates. Tighter monetary conditions in the world’s major economy will act as a dampener. Cycles of higher interest rates usually end in recessions; this one may prove the rule, with the Fed able to ease off the brakes with lower growth and inflation later in the year. As ever, we sing the virtues of quality, diversification and, wherever possible, value with a margin of safety. Our portfolios remain proudly and sensibly dull.

Sustainable Investing at Hawksmoor

One story that you cannot have escaped this year has been that of the use of plastics. Or more accurately, their misuse. The pivotal moment was the famous film of whales on the BBC’s Blue Planet II series, a piece of television that struck an extraordinarily powerful chord with the nation’s conscience. Sustainability has very quickly become a buzzword, not only of the media but also of the investment world.

Sustainability, in all its guises, is a topic we take very seriously in Hawksmoor. This is true of both our own business and also increasingly our investment style. We are very keen to improve and develop our own Hawksmoor culture of sustainability and responsibility. How can we recycle better? Can we power and light our offices more efficiently? Can we reduce business mileage? Can we change our sourcing and supplies to be more sustainable? How can we better support local initiatives and charities?

Last year we launched an Ethical Portfolio Management Service, which we believe is one of the first of its kind in the discretionary management industry. This follows all of the investment disciplines of our ‘mainstream’ service, but invests into equities and funds selected on their sustainable and ethical merits, as well as their financial prospects. We are also increasingly using these stocks and funds within our mainstream portfolios.

Our aim in choosing these equities and funds is not only to avoid products such as single-use, non-recyclable plastics, but also to identify those that make a positive impact. This may be as direct as renewable energy, but also encompasses businesses setting best standards in, for example, the fields of governance, equal opportunities, protection of supply chains, recycling and the management of waste, community support and education, and charitable work.

Most recently, we have launched an adjunct to our Model Portfolio Service. This is aimed at Financial Advisers with clients with smaller sums of money to invest than would typically be the case for our discretionary services. This new Model Portfolio allows these investors the opportunity to invest on an ethical and sustainable basis.

If you would like to know anything more about sustainable investing within Hawksmoor and how this could help you, please do contact your Investment Manager, who will be pleased to discuss this with you.

Jim Wood-Smith – Chief Investment Officer, Private Clients

Jim Wood-Smith – Chief Investment Officer, Private Clients

Tobacco

It is a near trillion-dollar industry that counts 20% of adults globally as its customers. It also currently pays £6 billion of the UK market’s dividends (FactSet). Yet investing in tobacco is clearly divisive: funding the leading cause of preventable disease and “the only legal consumer product that, when used as intended, will kill half of all long-term users” 1 is, for some, to do Beelzebub’s work. For those of a more libertarian persuasion, such protests unduly trample over personal choice, are inconsistent and preclude otherwise attractive opportunities. Herein we attempt at a balanced view of the state of the industry and its trajectory.

Big Tobacco is still highly profitable

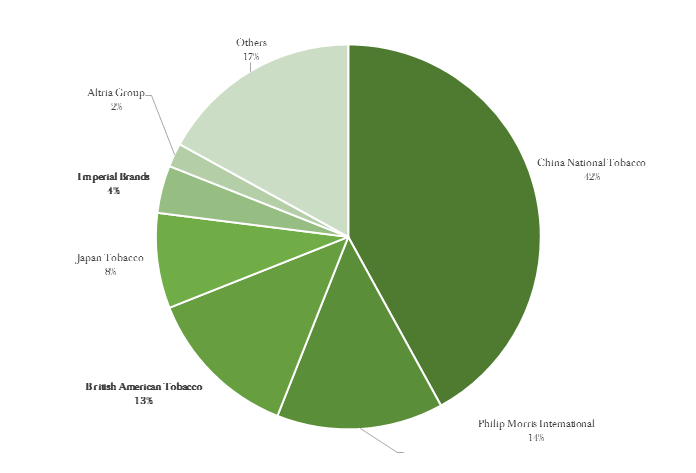

The economics of the major tobacco manufacturers are – or at least have been – unquestionably enticing. More than one billion consumers regularly buy their product regardless of the economic climate or price. Cigarettes are cheap to produce and transport, growers have little bargaining power, and bans on advertising inhibit new competitors from entering the market, so saving a packet on marketing. Brand loyalty is strong and market positions are well entrenched amongst a handful of players (Chart 1). These factors foster very profitable businesses: British American Tobacco, for instance, earns net margins of around 30%.

Chart 1: Global cigarettes volume share, 2016

Source: Euromonitor

A global perspective

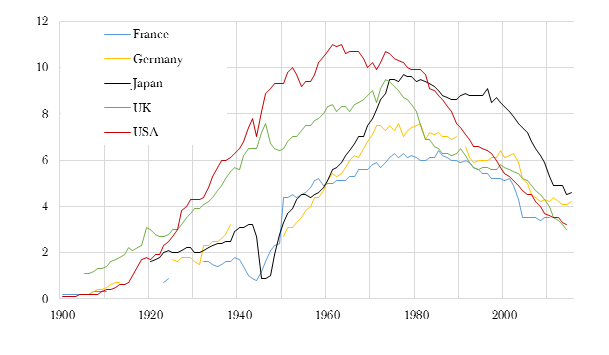

Smoking prevalence in the US, Western Europe and Japan has declined rapidly since the 1980s (Chart 2) due to greater awareness of health hazards and effective tobacco control policies, such as advertising bans, taxation and smoke-free workplaces. Success rates for quitters are at an all-time high because of changes in culture and better access to support.

Despite these developed market trends, at the global level the tobacco market is still growing. Falling volumes here are more than offset by emerging markets and their population growth, rising disposable incomes and a less stringent regulatory environment.

Chart 2: Sales of cigarettes per adult per day since 1900

Source: International Smoking Statistics (2017)

Tobacco and the public purse

The UK Government collects c. £12 billion in tobacco duties and VAT each year (Source: TMA), which is about 2% of total revenue (plus indirect sources, such as income tax from industry employees). Estimates for NHS spending on tobacco-linked treatments range from £3 billion to £6 billion annually, though there are other costs, such as cleaning butts off streets or tax lost from illness-related falls in productivity. The full calculation is even more difficult: we need to guestimate a patient’s cost to the NHS had they not smoked. Non-smokers tend to live longer and so, arguably, end up with greater healthcare costs over their lives.

Economic considerations are certainly not the sole factor (though in certain emerging markets where tobacco duties contribute up to 10% of government income, the economic arguments are rather more forceful). In the US, which accounts for 14% of retail tobacco sales (Euromonitor), authorities are stepping up the battle against smoking by proposing to limit the nicotine permitted in a cigarette. Their aim is to reduce addictiveness to assist even more consumers to quit. Were such a policy to be introduced, we would expect a sharp reduction in both the number of smokers and the daily volume of cigarettes consumed. In other words, this would super-charge the decades-long decline in the US tobacco industry.

The major caveat is that by law in the US tobacco policies must be science-based (most other countries can rely on mere whim and prejudice). Therein lies the challenge: authorities must prove that a nicotine standard will not encourage users to migrate to more harmful products (such as cigars or roll your own), nor that consumers will compensate with bigger drags or smoking more, nor that it will encourage an illicit trade in full-strength product. Expect legal challenges, an economic assessment from the Treasury, and a statutory mandated delay of up to two years so the industry can adapt. At the earliest, then, a nicotine standard could be five years away.

Next Generation Products (NGPs)

NGPs are heralded as the industry’s potential saviour against low or declining cigarette growth. Today NGPs account for around 2% of the tobacco market (over 90% is cigarettes), though that is forecast to double by 2021 (Euromonitor). British American Tobacco has spent $2.5 billion on its own suite of NGPs and has a 30% revenue target by 2030.

NGPs split into two main sub-categories: vapour and heated tobacco products. The former, which creates a vapour by heating liquid nicotine and flavouring, is by far the larger. The latter is most relevant in Japan where it is illegal to buy or sell liquid nicotine. Little research is available, though it is generally accepted both are less harmful than cigarettes and are an effective means of quitting altogether. Heated tobacco is the more controversial since, unlike vapour, it still contains tobacco. It is heated at a much lower temperature than cigarettes, which is believed to reduce the number of toxins inhaled while still delivering on the taste.

The competitive nature of NGPs is starkly different

Shifting competitive sands

Nascent NGP markets may offer an avenue for growth for tobacco manufacturers, but note that the competitive nature of these markets is starkly different to that of cigarettes.

First, barriers to entry. Since NGPs do not have the same restrictions on their marketing and brand loyalties are yet to be entrenched, the door is wide open for new market entrants. In the US, for example, the leading vapour brand is JUUL with a 60% market share (Nielsen). JUUL was spun out of PAX Labs, which was only founded in 2007.

The second issue is that Big Tobacco has an image problem. It is not ‘cool’, it is commercial and perhaps even a bit evil. New entrants, like JUUL, have a clean legacy-free image. Buying up trendy young companies doesn’t work either: as with craft beer, to the consumer’s eye the acquired inherit the corporate stain. Firms must tread a fine line: marketing an appealing product without the regulator feeling that they are targeting the youth (the FDA for example has spoken out against youth-led flavours like “gummy bears”).

Third, the favourable cigarette economics discussed above don’t all hold for NGPs. Even if successful, the additional marketing and development costs required dampen the margins and expected returns (although there is at present generally a price, and hence margin, advantage to NGPs due to the absence of excise duties). And remember that these products help users quit: the flip side of their growth is that they likely hasten declines in overall consumers.

On the other hand, Big Tobacco is well placed to compete in NGP markets since it has the capital, manufacturing capacity and importantly the supply chain networks. It may be simple to commercialize an e-liquid blend, but launching a new device requires substantial capital investment. The incumbent tobacco giants have shown they can adapt. Philip Morris’ IQOS, for example, commands an 80% share of Japan’s heated tobacco market. Imperial Brands’ innovative nicotine salt product myblu, combined with its e-liquid collaboration with Cosmic Fog, is recognised as one of the strongest new propositions in the e-cigarette market.

An attractive investment?

A number of readers will have an ethical aversion to ever investing in tobacco stocks, irrespective of price (and by using our bespoke portfolio services, you can steer your Investment Manager accordingly). From the stone-cold perspective of financial analysis, however, there is definable value in the future cash flows of these businesses.

Concerns over falling cigarette volumes, the implementation of a nicotine standard in the US, and the economics of next generation products have recently led to sharp falls in tobacco share prices: their previous premium ratings relative to the wider market are now substantial discounts (Factset).

While these are valid concerns, current share prices now discount very severe outcomes. Change is coming, though from growth in emerging markets to the potential of NGPs, an investment case cannot be stubbed out just yet.

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

This document is issued by Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered address: 2nd Floor Stratus House, Emperor Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon, EX1 3QS. Company Number: 6307442. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person in respect of any investments described nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice for which you should consult your financial adviser /accountant. The information and opinions it contains have been complied or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy. Hawksmoor, its directors, officers, employees and their associates may have a holding in any investments described. Any opinion expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic

context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation. They are subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can fall as well as rise. You may not get back the amount your originally invested. HA2582