Into this world we’re thrown.

– The Doors, Riders on the Storm (1971)

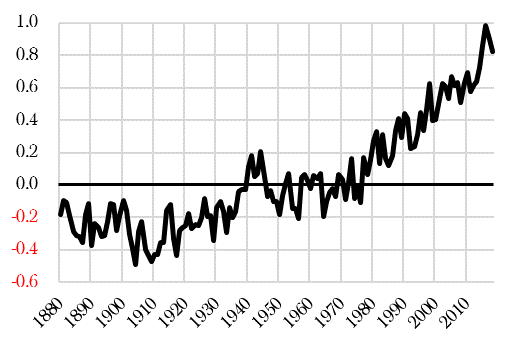

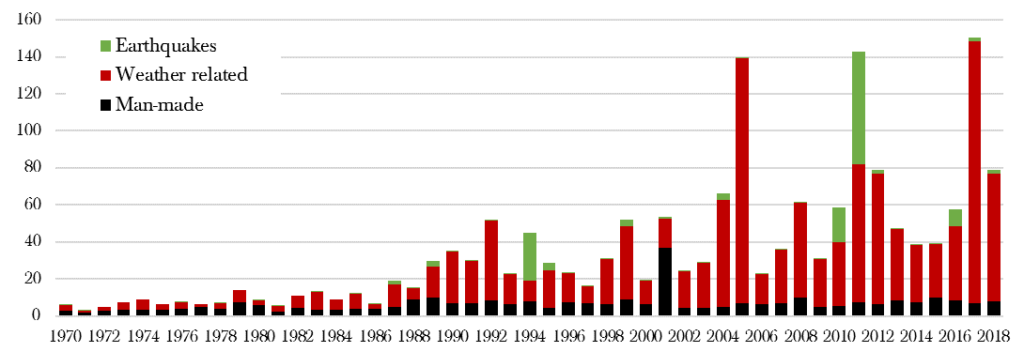

Earth’s climate is changing (Chart 1). This is creating more erratic and extreme weather, a tangible financial risk for businesses and individuals: 2018 was the fourth most expensive year for insured catastrophe losses, and 2017/18 was the worst ever two-year period (Chart 2). At the battlefront of climate risk is the catastrophe insurance sector. Its greatest challenge is to price accurately that risk in an increasingly volatile world.

Chart 1: Global surface temperature anomaly, annual mean

Source: GISS Surface Temperature Analysis, NASA

Known Unknowns

The climate is a notoriously difficult thing to predict, not least because we have no experience of a planet with average temperatures so high: we are in uncharted (warmer) waters (Chart 1). Studies conclude, however, that warmer sea temperatures and higher sea levels create hurricanes with maximum wind speeds up to 11% faster and with on average 20% more precipitation (Source: GFDL). Faster winds and more aggressive downpours will generally mean far greater damage to property during hurricane season.

The frequency of hurricanes is also on the rise. In the North Atlantic Basin, the long-term (1966-2009) average number of tropical storms is 11 annually, with 6 becoming hurricanes. More recently (2000-2013), the average is 16 tropical storms per year, including 8 hurricanes.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to lament society’s sluggishness on climate risks, yet for insurers with capital on the line its implications are more urgent. Catastrophe modelling is a specialism that began in earnest after 1992’s Hurricane Andrew caused $15.5bn of insured losses and 13 insurer liquidations. Whilst models previously relied on databases of past events, climate change means the next decade’s weather probably won’t just be a rerun of the past.

Insurers therefore today employ teams of climate scientists to create highly complex forecasting models. The challenge is the added uncertainty: small assumption changes may increase hurricane severity, yet might also divert their usual paths. A 2015 MIT study, for example, found a rising chance of a hurricane entering the Persian Gulf, home to a wealth of oil assets. Added uncertainty necessarily means higher premiums; there is a chance that property in coastal regions becomes too expensive to insure at all.

The Insurance Cycle

A major catastrophe forces insurers to pay out large claims (as with Hurricane Andrew, sometimes to the extent under-capitalized insurers go bust). The result is less capital at a time when people are anxious to ensure they are insured, which pushes up prices. Highly profitable insurance can be written and, should this continue in a relatively low claims environment, capital is lured back in by the high returns. Competition means prices fall, potentially to uneconomic levels. Then a catastrophe occurs and the cycle starts again.

The irony therefore is that well-capitalized insurers welcome periods of higher claims since it wipes out excess capital and leads to better returns. After all, were there no catastrophes, there would be no catastrophe insurance industry.

Chart 2: Global insured losses since 1970 (billion USD, inflation-adjusted to 2018 prices)

Source: Swiss Re Institute

Cat bonds and the hunt for yield

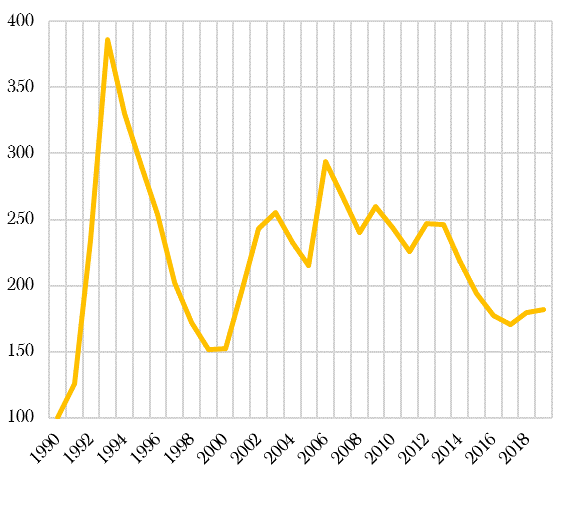

At least, that’s the way the cycle is supposed to work. More recently, the insurance cycle appears broken: despite the single worst two-year period for claims ever, renewal prices for catastrophe insurance have barely flinched (Chart 3). Prices do not seem to be factoring in what we know about how uncertain and extreme weather has become.

One explanation is a flood of new capital from catastrophe bonds and insurance-linked securities. Cat bonds are high-yield debt instruments that enable the issuer to waive payment of interest (or even principal) if it suffers a predefined catastrophe loss. These securities were formed in response to the prolonged period of low yields on traditional assets, coupled with a desire to find investments that are uncorrelated to equity markets.

At the end of 2018, insurance-linked securities amounted to almost $100bn of additional capital, a five-fold increase in the last decade. The worry is that the ‘hunt for yield’ is compressing prices right at the time when prices are inadequately allowing for climate change-related risks.

Chart 3: Global Property Catastrophe Rate-On-Line Index

Source: Guy Carpenter & Company LLC

The caveat is that one must distinguish between reinsurance and speciality lines. Reinsurance (insurance for insurance companies) is more capital intensive and increasingly commoditized. It is into these areas that the capital from cat bonds can effortlessly flow. Speciality insurance is more difficult for capital to access since it is typically smaller ticket, bespoke and requires a franchise and distribution network. Our strong preference in the current environment is to invest into the specialists, not the reinsurers.

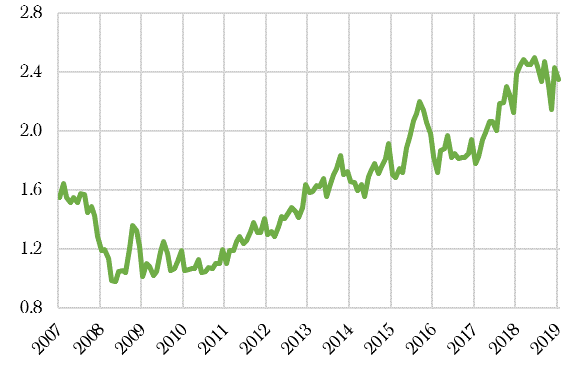

Valuation worries

A further concern is that current company valuations are elevated relative to history (Chart 4). Some reinsurance stocks are expensive regardless of the persistently subdued insurance rates and the recent high claims environment.

Chart 4: Lloyds underwriters, Price to Net Tangible Assets

Source: FactSet / Hawksmoor Research

Summary

Changes to our climate mean that we are living in a world with more volatile weather. For the insurance industry, this is not necessarily a bad thing: greater uncertainty and risk implies a greater need for the industry’s services. Ironically, insurers may be the surprise beneficiaries of climate change.

That, however, is only true to a point: insurers need to be able to assess the likelihood of various loss events to set profitable insurance rates. The greatest challenge for insurers is doing so in an increasingly unpredictable world.

Moreover, there is nothing in current rates to suggest the industry has yet updated its expectations for heightened climate risks, exacerbated perhaps by new capital sources. Every insurer insists that they carefully manage the cycle for returns, though history suggests most will still fail to write less business when pricing is poor.

Investors in insurance shares face stubbornly weak rates, prospects of the most extreme weather in modern human history and expensive share prices. This is not a recipe for an adequate ‘margin of safety’. Regrettably, it may take an unimaginably large loss event to reset premiums, share prices and expectations in this changed world.

Ian Woolley – Senior Investment Analyst

Health Warning/ Disclaimer

This document should not be interpreted as investment advice for which you should consult your independent financial adviser. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Any opinion expressed, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation. They are subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited is registered in England No. 6307442 and its registered office is at 2nd Floor, Stratus House, Emperors Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter EX1 3QS. HA3244

FOR PROFESSIONAL ADVISERS ONLY AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED UPON BY RETAIL INVESTORS