For Whom the Bell Tolls

Few will look back on 2018 with affection. A year that began so brightly ultimately ran away with itself and ended with equity market falls uncomfortably reminiscent of 2008 and 2009. That, we are glad to say, is where the similarities with the Great Financial Crisis begin and end. Financial markets have had an arguably overdue troublesome patch, but there is little reason for this to develop into anything of long-lasting significance. Our New Year message is to keep the seatbelt safely tightened, and that December’s storm will blow itself out.

This time last year we argued that while there was much that gave us hope for the year ahead, our greatest fear was that of valuation. That fear is what has ultimately reversed the direction of equity markets around the world; the bull market of a near decade’s standing has run out of puff and can no longer survive on hope alone.

We shall first try to explain what it is that has changed so dramatically over the past quarter before attempting to persuade you not to be overly concerned. For approximately half of last year we saw a rare divergence between the United States and everywhere else. It is usual that where Wall Street goes, the rest of the world duly follows. But for much of 2018 American equities rose apparently in defiance of elsewhere across the globe. We and others asked the rhetorical question of whether the gap would close in a good or a bad way? The question has been answered.

Here in the UK we have the additional parochial inconvenience of Brexit. That though is a fan on the flames of falling equity markets, it is not the cause of the fire. The spark that lit the flames was the fear of a so-called ‘trade war’ between the United States and China. We are not in the blame game, and it usually does take two to tango, but the prospect of the two largest economies in the world slapping each other with their designer handbags has frightened investors from California to Jiangsu.

Few will look back on 2018 with affection

Investors see slower economic growth in 2019 as a result. That means company profits below previously optimistic expectations and that, in turn, requires lower equity markets. That is especially pertinent when the starting point was, as we argued twelve months ago, already expensive.

Financial markets are moved just as much by hopes and fears as they are by reality. Indeed, economies themselves thrive and founder on the same frail sentiments. Fear alone is enough to put both economic growth and equity markets into a spin. And that is precisely what we are currently seeing.

The potential impact of the feared ‘trade war’ becomes so much greater against the backdrop of weaker Chinese economic data, rising US interest rates, a split US Congress, a divided Europe and a number of Emerging Markets struggling to pay their US dollar-denominated debts. Amidst this multifarious cast of uncertainty, the resilience of the US economy and the consequent prospects for corporate earnings had shone like a beacon. Markets, though, had forgotten John Donne’s words from almost 400 years earlier, that “no man (nor economy, nor stock market) is an island entire of itself ”.

It is the thick end of four decades since I was first made to study the metaphysical poets. I am delighted still to be able to put my long-distant education to work. I thus thank Slick Rick, as my English tutor was affectionately known, and apologise to John Donne for ruining his masterpiece: “and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls, Mr Trump; it tolls for thee.”

I have included American interest rates as part of the backcloth rather than being central to the action. That may be unfair on the Federal Reserve, as markets have a genuine fear that the cycle of higher interest rates will result in a recession. This is important, as it surprisingly leads us to happier prospects.

Central Banks have plenty of ammunition to counter a slowdown

Despite what some may argue, Central Banks have plenty of ammunition to counter a slowdown. This is especially true for the Federal Reserve. The key is that, with one notable exception, inflation is not a problem. That exception is the UK and is Brexit-dependent. And as we write this article, Brexit is still as clear as the thick December fog that has enveloped the West Country: so we move on. With precious little inflation with which to concern themselves, Banks are free to respond quickly and aggressively to slowing economic growth. Those that have already raised interest rates can reverse the increases. All can re-start and expand quantitative easing should they so wish.

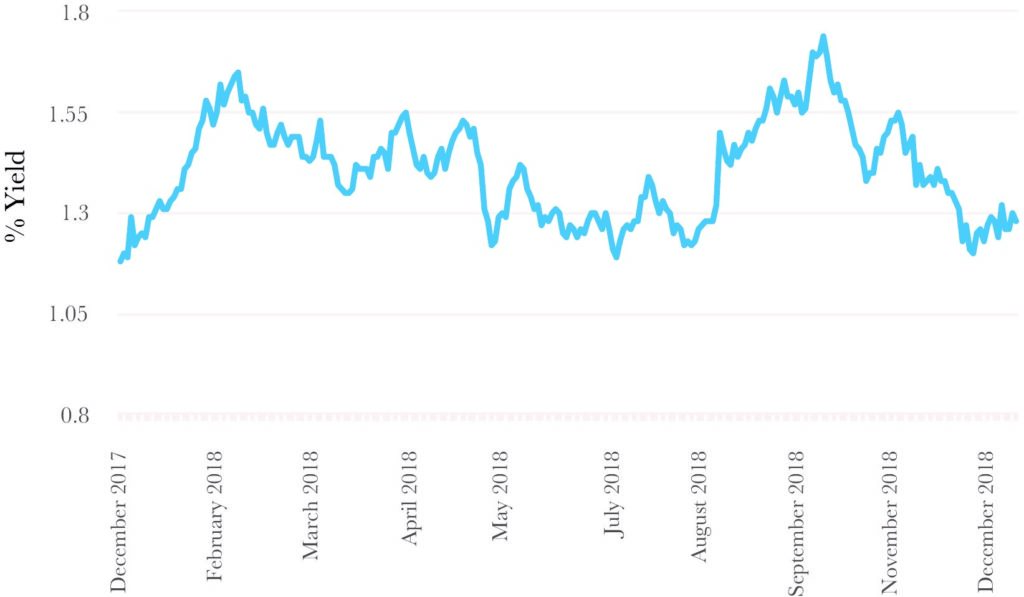

We tend to avoid spending too much time explaining bond markets. Despite bonds playing a hugely important role in very many of our portfolios, they typically fail to elicit a great deal of interest. They have nevertheless played an important steadying role in 2018. The lack of inflation and the fears over falling economic growth have combined to keep yields low. The yield on the US 10 year Treasury bill has ended the year at the same level as late January. The same is true of the UK’s 10 year gilt, while European yields have typically fallen, led by German bunds.

Chart UK 10 Year Gilt Yield in 2018

Source: FactSet

You will have noticed that, bar one lapse of concentration, we have thus far avoided Brexit. The end game is in sight. We have our best guess as to how this will all end, which we keep to ourselves, lest a) we are wrong and b) we cause apoplexy amongst half our readership. We remain of the view that No Deal is likely to be extremely poor for the economy in the short to medium-term and that portfolios primarily need to maintain their protection against this – via both non-sterling assets and an allocation to the safest investments – until we can be sure it is not going to happen.

We also refrain from entering the Brexit moral pulpit. Instead, we try to look to a time beyond it – whatever its incarnation – and the opportunity for businesses and markets to move on again. Should the UK avoid the worst of the risks from our departure from the EU, many domestic shares are priced at valuations we have not seen since the worst days of the Great Financial Crisis. That is something that is equally visible to the rest of the world, and their spouse. Neither will it be lost on them.

Regrettably, there is a caveat to even this train of thought: Jeremy Corbyn. The leader of the Labour Party has become synonymous with a much larger public sector, nationalization and a distributive fiscal policy. Whatever one’s political leanings, it is highly unlikely that the markets would take a potential Corbyn premiership well.

Just as a year ago we feared that the perpetual imbalance of risk and reward had swung too far in favour of the former (too much risk for too little reward), so we now see the scales moving in the other direction. In 2018, it took until the final quarter for gravity to take hold. The same may very well be true this year and we are likely to be in for some rocky times before the way ahead clears. But clear it will.

Jim Wood-Smith – Chief Investment Officer, Private Clients

Cleaning Up

2018 was a seminal year for recycling. The national conscience has finally awoken to the demanding issues of environmental sustainability, the impact plastic waste has on the world’s marine life (with at least some credit due to Blue Planet II) and a belated realization that our waste is not someone else’s problem.

Concurrently – and another key reason why plastic waste is suddenly top of the national agenda – are the consequences of China’s “National Sword” policy. This policy is rewriting the rules of the recycling game in profound ways.

National Sword

For decades, developed nations have used China as a dumping ground for their excess waste. In 2017 China processed 55% of the world’s scrap paper and imported 3.5 million metric tonnes of scrap plastic. Virtually all UK plastic recycling is exported: and China used to be the main buyer.

Yet with mounting concerns over air quality, pollution and illegal waste smuggling, the Chinese government launched National Sword, a campaign against jang laji (“foreign garbage”). Crucially, from January 2018 this policy banned outright the importation of 24 types of waste materials and set much higher contamination standards for the rest.

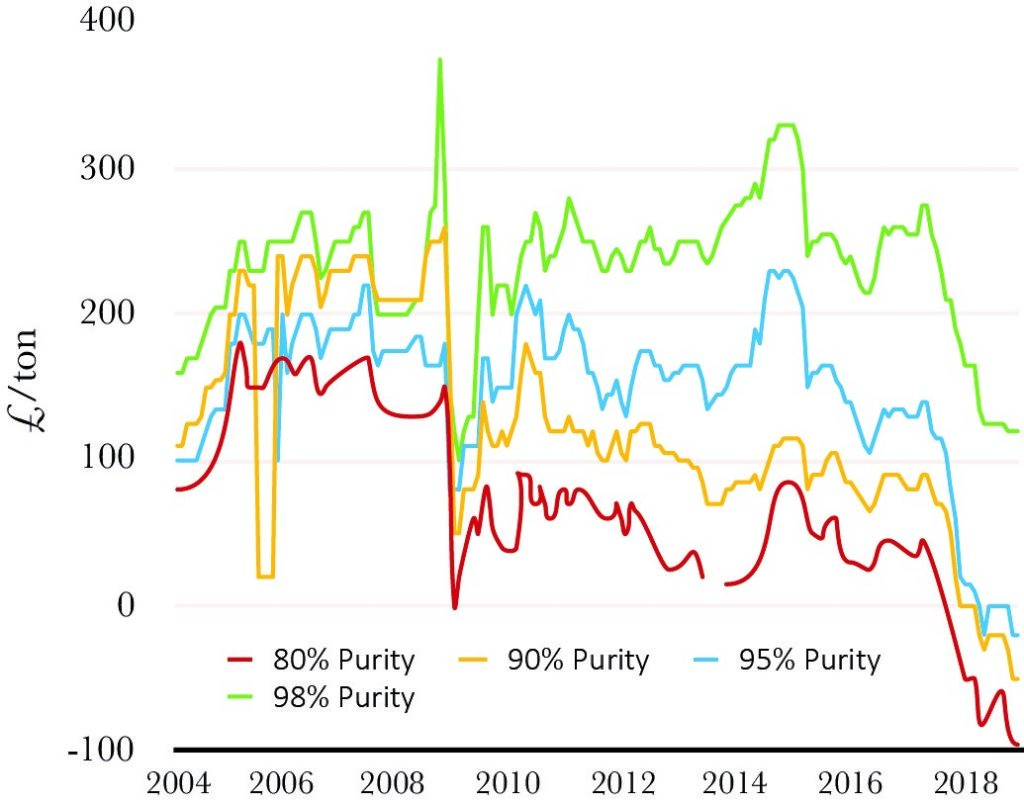

The market impact was savage. With the key buyer of scrap paper and plastic removed, prices collapsed (Chart 1). That took much of the profitability away from the UK’s Material Recovery Facilities, which take in raw recyclable waste, separate and process it into a commodity. That loss of revenue has only been partly mitigated by higher gate fees levied on the collectors of waste.

Chart 1: Recycled plastic prices, Jan 2004 to Sept 2018

Source: LetsRecycle.com

The challenge of National Sword is exacerbated in Britain due to the relative immaturity of our recycling infrastructure. Our curb-side recycling collections are mostly mixed: though sorted, contamination is naturally high and that produces a low-grade commodity. Our European cousins are much better at this. The importance is that National Sword increases standards from 90–95% purity to 99.5%. Notice in Chart 1 that purer recycling grades are attributed higher prices and that this year prices for lower grades actually turned negative.

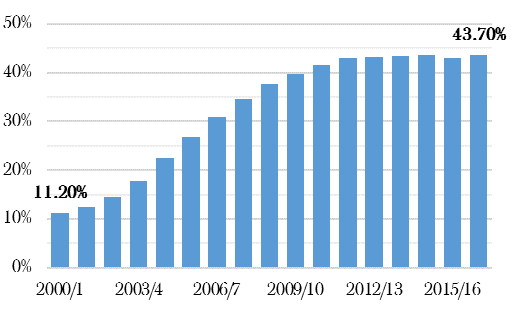

Some of that excess has gone to other Asian markets, such as India, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand, pushing them past capacity. We know 90% of the plastic in the oceans comes from ten rivers, eight of which are in Asia. Otherwise, after decades of positive progress (Chart 2), more of our recyclable waste is at risk of simply ending up in landfill.

Chart 2: Household waste recycling rate in England

Source: Defra Statistics¸2000/01 to 2016/17

In summary, the UK became accustomed to exporting relatively low-grade recyclate to the Far East. There hasn’t been the pressure to invest in our own recycling facilities, segregated collections or better sorting technologies. With the main buyer now regulated out of the market, that has to change. The UK needs to invest in its own recycling industry to realize a self-sufficient circular economy.

Energy from Waste

One of the alternatives to recycling our waste, or burying it in the ground, is to use it to generate electricity: an easily obtainable fuel that diverts materials going to landfills. Indeed, even existing landfill sites are today generating electricity through the trapping of methane gas emitted as the waste decomposes.

Yet be under no illusions: Energy Recovery Facility is generally a euphemism for incineration. That means emissions of toxic and hazardous pollutants: to produce 1MWh of electricity, an ERF produces more than twice the carbon dioxide than a natural gas plant. Around 25-30% of the waste remains as residual ash to be disposed of or stored and, of course, there is nothing circular about destruction

Recycling in the UK

Certain materials are simply easier to recycle. Packaging group DS Smith, for example, operates nine cardboard recycling facilities in the UK. As well as producing boxes, it collects, sorts and recycles cardboard from its customers to make new boxes. It is a complete circular economy model: DS Smith claims this cycle repeats every 14 days.

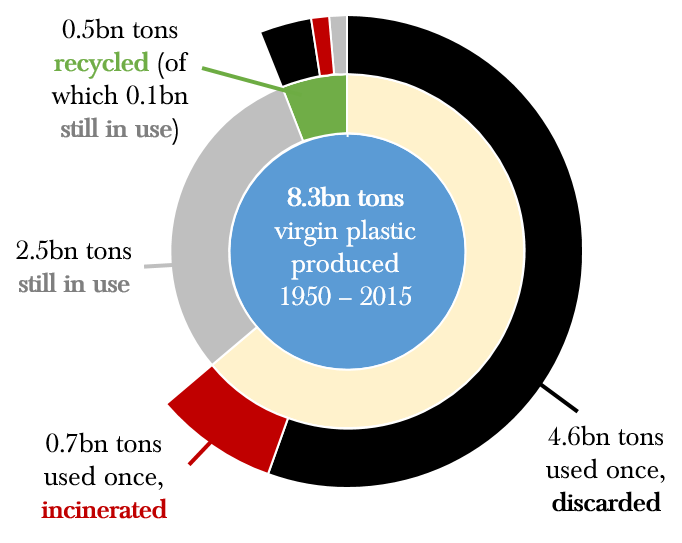

Plastic is more difficult (Chart 3), not least because there are over 50 different types – such as PET, HDPE, PP and PVC – that generally need to be sorted and processed separately. There is some incremental investment already happening in the UK: Biffa, for example, recently unveiled a £15m plan to open a PET recycling plant with an output of 25ktpa. However, it is small in comparison to that set aside for Energy for Waste: at the same time, Biffa is involved in a £270m project for 350ktpa of energy recovery plant. Our concern is that the economics of Energy from Waste are crowding out the investment and environmental needs of pure recycling plants.

Naturally, commercial organisations need assurance on the economics of projects and demand for recycled material before investing. We expect visibility on this to improve in coming years, especially with the introduction of a new tax on packaging containing less than 30% recycled content. Indeed, the tax’s stated intention is to make prices ‘so exorbitantly high’ that companies would simply conclude virgin plastic packaging was no longer worthwhile.

Chart 3: Fate of all plastics ever made 1950 – 2015

Source: R. Geyer et al., Science Advances

Then there is China: its economy will still have a huge appetite for plastic and cardboard. There are parallel repercussions of National Sword occurring within China and there has been little time to adjust. Instead of sending containerships of old boxes and bottles, perhaps in future we will send papers and plastics we have recycled ourselves.

Investment Considerations

Our core thesis is that the changes to the recycling landscape in 2018 pave the way for a significant improvement in the UK’s recycling infrastructure and technology base.

Naturally, this will create incremental construction work to build the recycling and energy recovery facilities. Yet this is not without significant risks: Interserve ran into huge financial difficulties building a Glaswegian Energy from Waste plant for Viridor. Construction is an industry with razor thin margins where complications, particularly when utilising new technology, can quickly turn contracts onerous.

UK-listed operators of waste facilities include Biffa, Pennon and Renewi. A greater need for recycling activity in the UK creates a structural growth opportunity for these businesses, especially when supported by government policy. However, these projects will require hefty inward investment: it will take time for that to translate into returns.

Our preference is to invest in the manufacturers of the equipment and the innovators of the technology. In August this year, Viridor announced it had installed a robotic sorter in its Skelmersdale facility that uses artificial intelligence and vision to identify recyclables and make decisions. Elsewhere, several firms are developing chemical processes to break down plastics back into a form of oil.

Direct investment options in the UK are limited: most are small private companies. We therefore prefer to access this theme via funds. As just one example, the Jupiter Ecology fund, which features in our Sustainable World service, holds a stake in TOMRA Systems, a US company pioneering sensor-based materials sorting.

Final thoughts

National Sword is hugely disruptive to the UK’s recycling industry in the short-term, though at the same time offers a real opportunity for the UK to finally take responsibility for its waste. We wish to invest in those companies at the forefront of transitioning our economy to a more sustainable future.

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

Ian Woolley CFA – Senior Investment Analyst

This document is issued by Hawksmoor Investment Management Limited (“Hawksmoor”) whose registered office is at 2nd Floor Stratus House, Emperor Way, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS. Company No. 6307442. This document does not constitute an offer or invitation to any person in respect of any investments described, nor should its content be interpreted as investment or tax advice for which, if you are an individual, you should consult your independent financial adviser and or accountant. The information and opinions it contains have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable at the time and are given in good faith, but no representation is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Hawksmoor, its directors, officers, employees and their associates may have a holding in any investments described. Any opinion expressed in this document, whether in general or both on the performance of individual securities and in a wider economic context, represents the views of Hawksmoor at the time of preparation. They are subject to change. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations. You may not get back the amount you originally invested. With regard to any of the Hawksmoor’s managed Funds, please read the prospectus and Key Investor Information Document (“KIID”) before making an investment.